Lipsticking the pig

Christopher Hitchens, the Great Iraqi Asparagus, and the friendship that sank two countries

Don’t allow your thinking to be done for you

by any party or faction, however high-minded.

Christopher Hitchens, Letters to a Young Contrarian

Get me a terrorist and some WMDs,

because that’s what the Bush administration wants!

Francis Brooke, consigliere to Ahmed Chalabi

“FATALLY UNRELIABLE,” “RUTHLESSLY DECEPTIVE,” “an inexplicable certitude in his own entitlement,” “a relentless and almost obsessive” chaser of “U.S. taxpayer funding,” weaving “Scheherazade-like tales,” “one of the great con men in history,” “not the best thing since sliced bread.”[1] Here in quick capsule form is the legacy left to us by Ahmed Abdel Hadi Chalabi. These quotes are the streamers flapping at the summit of his obituary, markers of a man who found a moment in history after 9/11 that matched his personality in its malice, its pointlessness, its mendacity. As chief of the Iraqi National Congress, as a peddler of influence, as a fabricator of conspiracies, Chalabi was among the few figures of whom it really could be said that reality was bent to their will. Edit Ahmed Chalabi from the snuff tape of the 2000s, rewind the cassette, and the War on Terror does not play back in the same squalid way.

Sure, if it came down to it and we were obliged to carry through the nasty but necessary business of attributing blame for the high-octane misery of the Iraq War, we would carefully align the guillotine’s edge over the napes of George W Bush, Dick Cheney, Paul Wolfowitz, Tony Blair, and the staff of the Office of Special Plans. They would be first in the queue; nose-to-tail in the VIP fast lane. Not far behind would be Ahmed Chalabi. Because beyond the White House and Pentagon, in the realm where theory is face-hardened into fact, in the machine more capable than any other of moulding opinion and extracting its consent for unhuman actions, he made the difference. And in this mission Chalabi was aided by Christopher Hitchens: perhaps the last true public intellectual, the scabrous prince of a time before he and others like him made a farce of that term and excavated it of all meaning.

To the outsider’s eye, to the public mind, Chalabi and Hitchens’ friendship was crucial. It combined authentic dissent and aggressive methods; on one flank the credentials of the righteous exile, on the other the heft of a skilled polemicist. Hitchens gave fangs to Chalabi’s grievance; Chalabi, in turn, gave legitimacy to the moral necessity of invasion. If you take Christopher Hitchens’ writings on trust (and there are plenty of reasons not to do that), he went to his death believing Ahmed Chalabi was a close friend and a fellow combatant. Over several columns in Slate, in the memoir Hitch-22, and on television, Hitchens spent a decade as a dutiful reservist in Chalabi’s public bodyguard. He dedicated his pro-invasion pamphlet A Long Short War to him – “Comrades in a just struggle and friends of life” – and persisted in praising a “very brave and extremely brilliant man” with a “genius for politics” who “made no grandiose claims.” That belief – dare we say faith? – was tougher than diamond, invulnerable to the crushing forces of evidence and fact.

But what kind of a friendship is it where affection flows only in one direction? when half gives and half takes? when one is admiring and the other conniving? The two men depended on each other, certainly, though only one of them was honest enough to understand why, and he was the least honest of the pair. Hitchens was as important an instrument for Chalabi’s schemes as Chalabi was for Hitchens’ sense of himself. In the moral and political diorama this Anglo-American transplant needed to justify an eternal, civilisational war, a suave and ingratiating Iraqi exile had to be the centrepiece and focal point. It was psychologically vital for him to believe Chalabi wasn’t a failed banker and fraudster-on-the-run but a Man of History, a Jeffersonian figure and a democrat down to his toes, attentive to the study of guerrilla warfare as well as literature and civil society.

Having spent the long, miserly, damp, cracked-up afternoon of the 1990s vibrating to the resonance of ideological emptiness and retreating from the movement that once sustained him, Hitchens found in Chalabi a miraculous antidote to loneliness – an agent of re-illusion, a beau ideal. Thinking himself a special case, independent and immune to the pull of grifters, he refused to notice he had been taken in, recruited to the ranks of well-placed and sincere dupes willing to carry through a criminal design.

WITH ALL THE PERFECT fuzziness of a former presidential speechwriter, here is David “Axis of Evil” Frum giving a rough sketch of an encounter with the His Eminence:

The first time I met Ahmed Chalabi was a year or two before the war, in Christopher Hitchens's apartment. Chalabi was seated regally at one end of Hitchens's living room. A crowd of nervous, shuffling Iraqis crowded together at the opposite end. One by one, they humbly stepped forward to ask him questions or favors in Arabic, then respectfully stepped backward again. After the Iraqis departed, Chalabi rose from his chair and joined an engaged, open discussion of Iraq's future democratic possibilities.

“Regally” is the operative word. As the favoured son of a merchant family once tightly bound to Iraq’s Hashemite dynasty, and even as he later mutated between professor, failed banker, then self-proclaimed dissident, Chalabi’s plump grandee sneer never left him, nor the gospel of entitlement and venality that is the rich man’s birthright. Balls to whoever those Iraqis were or what they were asking for, heads bowed to the fag-ashed parquet floor of 2022 Columbia Road NW, Washington DC; Frum’s snapshot gives us a pretty good idea of Chalabi’s attitude as between debtors and creditors. For other Arabs he would sit as a sultan and await their obeisance. To those he wanted to milk for access (or money) he played the velvet-tongued smoothie.

Chalabi possessed at most three gifts, each complimentary to the other. He was a gifted mathematician, a gifted liar, and a gifted charmer. The last of these was the most useful, particularly when he needed to invade and occupy a social circle. He could make anyone feel like the best version of themselves and was very good at flattering anxieties. Ask a question and Chalabi would praise you on the intelligence or insight of it. State an interest – the gossip of the Bloomsbury Set, Sufi music, the technology of oil drilling – and Chalabi could carry on a monologue just smart and fluid enough that insider and outsider alike felt stirred as well as validated. Impress enough of the right people in this way and your repute will stand before you like a pavise. “Give a man a reputation as an early riser,” Hitchens liked to say of Kissinger, “and he can sleep till noon.”

The trick with Chalabi was in never seeing all sides of his many fronts. To anyone he could be almost anything. For the wonk-hawk neocon crowd around David Wurmser and Douglas Feith, Chalabi played part of his true self: the Iraqi aristocrat unjustly vacated from his rightful place. He noticed their disguised passion for imperial fantasies and pitched himself as an enlightened monarch. To anyone in uniform, Chalabi would hone his slant such that any military man, thinking of their father’s generation, would clock the parallel with Charles de Gaulle and the Free French Forces marching into Paris. (De Gaulle’s nickname, given during the First World War on account of his height, was The Great Asparagus; Chalabi’s ‘Free Iraqi Forces’ were a haggard squad recruited from refugee camps who offended their American hosts by shitting all over their airbases). To the NGO crowd he spoke the dialect of rights and liberties; to his friends in Iranian intelligence he posed as a bullish sectarian.

The version Christopher Hitchens got to see, and which attracted him enormously, was the dashing, intellectual, romantic, almost Byronic side. Hitchens had an admirable weakness for the popular hero jailed or banished by a rough regime, the lone dissident scorned. He liked Václav Havel, and Willy Brandt, and Andreas Papandreou for their fortitude in exile, and hailed Chalabi as the latest in a lineage of brave liberators, the seductive twofer of man of action and man of letters. Indeed, as Hitchens explained, it was precisely a conversation about the Bloomsbury Set which convinced him of Chalabi’s charisma. Surely this ex-professor and outcast couldn’t be just another swindling thug, another chancer on the make? He fell hard, and thereafter, in his conspiratorial late-night get-togethers – Colin MacCabe recently described his apartment as a “war room” in this period – thought himself inducted into a rebellious sect. Really he had been taken in by an embezzler weaned on the teat of CIA lucre.

Like George W Bush in his youth at Andover, Hitchens was a cheerleader with pom-poms on.

There is no full biography of Christopher Hitchens yet, though a triplet of anguished and polemical books has tried to take the measure of his legacy and influence.[2] None of them grasped the depth of his self-delusion or the scale of mythmaking found in the memoir, Hitch-22. As IF Stone once said of funerals, autobiographies “are always occasions for pious lying.” Hitchens fudged dates, puffed up his importance, and pinged gently off the mantlet of criticism which, by 2010, was already stiffening into something resembling good history. In Hitch-22, fantasy slipped its leash.

Cowering behind the nervous laughter of two diversionary jokes (about Spike Milligan’s Adolf Hitler: My Part in his Downfall and his own side being a “multifariously sinister crew”), Hitchens would have you believe he and a small clutch of others came up with the idea for the Committee for the Liberation of Iraq, and that this “faction” or “combination of influences” was how “political Washington was eventually persuaded that Iraq should be helped into a post-Saddam era.” Hitchens is so precise in his imprecision that you’d be forgiven for thinking the Committee was formed circa 1998, when he first met Chalabi and the Iraq Liberation Act was being passed, that he was present and involved at the moment American policy was coalescing into an explicit and overt demand for Saddam’s overthrow.

In fact, the Committee’s origin was in the White House, specifically the desk of deputy National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley who wanted a non-state, non-Iraqi-exile organisation to bolster the Bush Administration’s case from the outside. This was in the autumn of 2002, already late in the day, and its chief organiser was the former Lockheed Martin stooge Bruce Jackson. Not a grassroots squad, then, or even independent at all but deeply implicated in the Bush regime’s designs. And in the Committee’s moral emphasis on Saddam’s atrocities as the casus belli there is a hint the group was being used to shore up an argument so far dependant on the (fraudulent) WMD question and the dictator’s (fraudulent) links with al-Qaeda (more on which later). This is not, as Hitchens would have it, “an account of what we did and why we did it,” a refutation of the “lurid invention” and “paranoid disinformation” he imagines as behind the condemnation thrown his way. It is the opposite. Hitchens insisted he was in the engine room, shovelling coke into the furnace. Really, like George W Bush in his youth at Andover, Hitchens was a cheerleader with pom-poms on.

SINCE IT ALL WENT so catastrophically bad, and the menaces who led the “Coalition” into Iraq in March 2003 have been made to feel slightly uncomfortable, newspaper columns have occasionally quivered with the wet sounds of mercy pleas. The pained cry of the hawk-turned-chicken crowd takes two forms: we invaded for the right reasons but it turned out poorly; we invaded on the pretence of a lie but were right to go in one way or another. In defence of this worming, and in a not dissimilar manner to Hitchens’ protection racket for Chalabi, Matt Johnson (author of How Hitchens Can Save the Left) has tried to split these twin strakes of a strategy into separate actions. “Though [Hitchens] often made indefensible arguments in favour of these wars,” Johnson wrote in a plea for ‘heterodoxy’, “his central argument ways always his view that universal human rights should be upheld around the world.”

But the matter of universal rights cannot be extracted out of the WMD question, nor the WMD question from the rights matter; each combined to make up the whole. The existence of chemical or biological weapons was proof, the argument went, that Iraqis needed to be pulled out from under a grubby regime; their ‘liberation’ necessitated the destruction of those same weapons. The hysterical, febrile atmosphere of the 9/11 years forbid half-measures or hair-splitting. The frisson of the insider at the imperial core, the thrill of creating reality as actors of history – they all felt it, back then. And anyone trying to scalp a good intention from the carcass of the war is only making a bid for their own exoneration. To modify slightly something Robespierre said: democracy cannot be delivered like a warm pizza on the flat of a bayonet.

Edit Ahmed Chalabi from the snuff tape of the 2000s, rewind the cassette, and the War on Terror does not play back in the same squalid way

To the very end Hitchens was lipsticking the pig of the invasion. If he ever felt he had been press-ganged into a crime, if he noticed the whiff of Tonkin Gulf about the whole operation, that concession went unprinted. Long past the hour when he should have been shutting well up, Hitchens went on defending the quality of evidence the United States and Britain relied on to mutilate a country. From a November 2005 column:

What do you have to believe in order to keep alive your conviction that the Bush administration conspired to launch a lie-based war?...[The Iraqi National Congress] was able to manipulate the combined intelligence services of Britain, France, Germany, and Italy, as well as the CIA, the DIA, and the NSA, who between them employ perhaps 1.4 million people, and who in the American case dispose of an intelligence budget of $44 billion, with only a handful of Iraqi defectors and an operating budget of $320,000 per month. That’s what you have to believe.

That “$320,000 per month” figure is an interesting one. It was the amount given to the Iraqi National Congress specifically for its ‘intelligence’ operations by the State Department (as mentioned in a contemporaneous 2002 report in the New Republic). For its day-to-day running, however, the INC was getting three times more than that – $33million between 1999 and 2002. Hitchens’ plea of minnow against whale in this passage is wrong in fact as well as spirit. The amount of “$320,000 per month” was also, strangely, the exact figure Chalabi was receiving during his first stint as a CIA asset in the early 1990s. The numbers are a coincidence, but did Hitchens know Chalabi had once been in bed with Langley? not just in bed but engaged in enthusiastic heavy petting? If he did, he never mentioned it. Anywhere. There was no excuse for him not to know. Peter Jennings had revealed Chalabi’s CIA funding on ABC in June of 1997, a detail easily confirmed if Hitchens cared enough to do the barest minimum of due diligence on his ‘friend’. The journalistic duty of getting your stuff at least in the ballpark of being correct was one of the many principles he would freely violate.

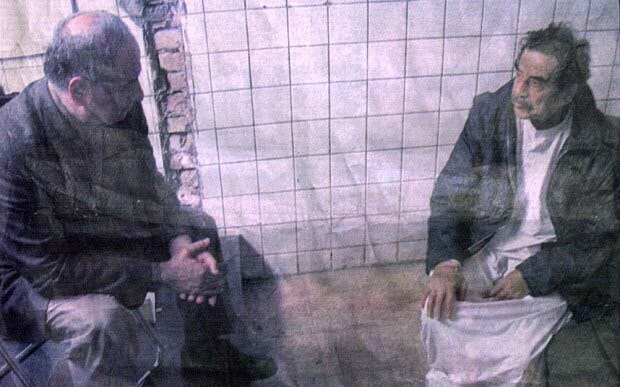

Part of Chalabi’s role as a CIA man between 1991 and 1996 was to run a propaganda operation: a newspaper, a radio station, and an intelligence network to generate dissent and dissatisfaction in Saddam Hussein’s army. The plan, supposedly, was to cultivate defectors in the Republican Guard who, when the time for a revolution came, would instantly turn rebel and lend their legitimacy and military expertise to the cause of Baathist overthrow. It was a spectacular failure in that regard, but after 2001, Chalabi turned these techniques back on the Bush administration. He wanted gossip, scoops, and rumours that would fill in the black hole where America’s knowledge of Iraq should have been. And he did not have to fight very hard for attention. “We didn’t go to the Bush administration,” Chalabi said later. “They came to us.”

A triplet of sensational ‘intelligence’ reports curated by the INC’s spook office – the Information Collection Program, run by Arras Karim Habib – were the most important in bolstering the case for invasion. They found a colonel who claimed, on the record, that some of the 9/11 hijackers were trained on the rusty hull of a Boeing 707 parked in Salman Pak, a few miles south of Baghdad. That was twaddle. Next they pushed a ‘defector’ who ‘knew’ about a fleet of trucks and railway cars that endlessly toured the Iraqi countryside churning out Sarin and VX – and that these gasses were sold to al-Qaeda. This was hogwash. The ICP was pushing it a bit when they got a Greek woman to go on camera and spill the beans on Saddam’s sexual fancies – she then blurted out, unprompted, that Hussein and Osama bin Laden were pals. When combined with the fabrications that did not come from Chalabi (munitions concealment, Niger yellowcake, Curveball), the struts propping up the case for invasion were in place. Even if each story was quickly found to be a clanger, and they all were, their reliability was less critical than overall effect of a campaign. And Hitchens, like almost everyone else, was taken in. He waxed his cloth with the cons invented by Chalabi’s gang to shine the howler of a case for war.

The frisson of the insider at the imperial core,

the thrill of creating reality as actors of history – they all felt it, back then.

Judith Miller of the New York Times is justly remembered (and hated) for her role as the dutiful conduit for this junk. But in this scheme Christopher Hitchens’ belief was bolstered because it also came from within the magazine for which he was a star writer. From December of 2001 Vanity Fair published several longform ‘investigations’ by David Rose, as well as a fawning stenographer’s portrait of Chalabi that blindly recycled the man’s self-made mythos. Chalabi and the INC fed Rose the line, and he regurgitated it. His output was so influential in giving weight to the war’s necessity that the Bush Administration itself depended on it as crucial segments in the chain of evidence. The Silberman-Robb Commission Report (also called the WMD Report) published in 2005 noted how David Roses’s articles (specifically ‘Iraq’s Arsenal of Terror’, May of 2002) went verbatim into the all-important October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate without independent corroboration, after the DIA and CIA had already warned that Chalabi’s “defectors” were really “fabricators.”

The INC op didn’t need to dupe the spooks or “manipulate” them as Hitchens claimed; all it had to do was bypass the agencies. Chalabi’s channel went around the CIA and NSA and was plumbed directly into the Office of Special Plans, from there to desk of Dick Cheney, then into the speech Colin Powell gave to the United Nations on February 5, 2003. Worst of all, Hitchens knew this was a viable theory at the time and still described “the accusation about an alternative ‘stove pipe’ of disinformation” as failing to “hold much water (or air, or smoke).” (Note also the sad attempt to dodge a prose cliché, exemplary of how gummed with gunk his late style got). Meanwhile, depending on that same back-channelled evidence, he lent his shoulder in the scrum of thousands heaving the intellectual, political, and moral argument for war into the public sphere until it became a heresy to try and dispute it.

WHAT IS REMARKABLE IN interrogating the Chalabi-Hitchens ‘relationship’ is just how many first principles Hitchens sacrificed to it – principles he didn’t need to brutalise or abandon even in making his transgression to the Right. The rooms he entered in those years were thick with the types he had spent years writing against and trying to expose: spooks and confidence tricksters, bagmen and gun-runners, Olympic-level liars, political cynics, bankers, and the bastards of big business, all united in their fondness for sectarian stupidity, crass militarism, and underhanded lobbying.

An example. In the late 1980s the kingdom of Jordan was facing a financial crisis. To prevent collapse, its regulators ordered all banks operating in the country to deposit a percentage of their holdings in the central reserve. As chief of Petra Bank, Ahmed Chalabi refused. In contrast to what it said publicly, Petra barely had any cash, most of its millions instead sloshing around in various Chalabi family schemes spanning Lebanon to Switzerland to the Caymans. A Jordanian military court investigated. Part of the probe was an audit undertaken by Arthur Andersen who found “a massive compilation of lies or mistakes.” (That firm knew a thing or two about fraud: a few years later Arthur Andersen joined in a contract to help Enron cook its books). Chalabi fled when his scam was exposed, but in his ‘innocence’ claimed the military court was convened on Saddam Hussein’s orders. For the rest of his life Chalabi insisted he was the victim of conspiratorial frame-up.

So too did Charles Keating when his thievery was exposed in the Savings and Loan scandal of the same period. In the 1990s Hitchens would make much of Keating’s fraud as emblematic of Reagan-era financial debauchery and recited at length the sordid tale of Keating’s gift of stolen cash to Mother Theresa (who then petitioned the judge in Keating’s favour during sentencing). Hitchens also wrote about the connections between Savings and Loan banks and the morass of fundraising for covert actions that swirled between the CIA, the mob, Contra death squads, and Dubya’s daddy George HW. Compared to all that effort, Hitchens would insist to the end that Chalabi’s version of the collapse of the family empire was the correct one, defending him against the “bile and spittle” and “near-unbelievable deluge of abusive and calumnious dreck” of his (ultimately correct) accusers. As late as May 2004, he confessed “I do not know what happened at the Petra Bank…[It] ought at least to be noted that Chalabi still maintains he can prove his case.” The closest analysis of the Petra Bank affair was compiled in Aram Roston’s biography of Chalabi, published in 2008, yet still its subject refused to present anything that might exonerate him. Nor did Hitchens ever rescind his faith in his “friend” on the grounds of failing to fess up. He was, as George Scialabba sweetly put it, a “stubborn fucker.”

Did Hitchens know Chalabi had once been in bed with Langley? not just in bed but engaged in enthusiastic heavy petting?

Another example. A hefty bulk of the Minority Reports he wrote in the 1980s, and the first third of his collection For the Sake of Argument attacked the monstrous criminality of the American intelligence system – a “state within a state” and the “ghost in the machine” immune from censure, prosecution, or democratic control. Yet two of Ahmed Chalabi’s closest aides in the late 1990s were James Woolsey and Duane ‘Dewey’ Clarridge. The former was CIA chief under Bill Clinton who on September 12, 2001 was going on television to free-associate about Iraq as responsible for the atrocities of the day before. Clarridge was a filthier beast: perhaps more than Colonel North, he was the architect of the Contra side of the Iran-Contra scheme and likely would’ve gone to prison for perjury had Poppy Bush not pre-emptively pardoned him. Handling PR for Chalabi and the INC, meanwhile, was the firm of Charles Black, Paul Manafort, and Roger Stone. Their lobby shop was one of the many offices in the 1980s which formed the nexus of leftover Bircher and Goldwaterite fundraising with gay-fascist-operators, all while giving warmth and succour and White House connections to a run of tinpot dictatorships spanning Angola to the Philippines.

Guilt by association? Absolutely. But smaller scandals of lesser men with more tenuous connections than these were grounds enough for Hitchens to make an argument, once upon a time. And while it’s unknown if he was every pally with Clarridge and Woolsey at any number of the semi-official receptions or American Enterprise Institute banquets that were the locus of social life for the neocons, he nevertheless was tightly bound to achieve the same purpose, on behalf of the same man, as the sorts of people he had once committed himself to driving from public life.

The gravest insult for last. From the opposite end, insofar as his feelings can be discerned at all, Chalabi thought of Hitchens as just another asset to be cultivated. Hitchens’ name appeared on a notorious list compiled by the INC’s Information Collection Program, filed to their paymasters in the State Department as proof of the effectiveness of their persuasion and influence operation. “As I soon as I found out,” Hitchens said of his inclusion on the list, according to Douglas McCollom in the Columbia Journalism Review, “I wrote a friend at the INC to say ‘What the fuck is this?’” He swore too against using INC ‘defectors’ as sources for his own stories, but that wasn’t the point, and the reply – if it ever came – did nothing to smother his praise for the man who gave him a second life as a crusader for former enemies.

NOTHING WILL ALTER THE just and reasonable verdict rendered upon Ahmed Chalabi. He’s right where he should be, way down in the pit of ignominy. Since 2001, however, a low-level insurgency has been waged by both haters and admirers over whether Christopher Hitchens became a true neoconservative. It is a fruitless battle: of course he was.

Neoconservatism, from its beginnings in the Manhattan trenches of the post-Stalinist Left, was always a movement of converts. They may have abandoned much of their former selves, yet themes and tics persisted. They still believed in the malleability of the masses but the agency shifted: rather than the responsibility of the masses to change themselves, the neocons believed someone should do it on their behalf – usually the powerful, born to the role. They also refused, as a movement, to succumb to introspection or anxiety about their conversion, instead redoubling their efforts in a new direction. The neocon stars who burned brightest never indulged in the kind of self-flagellation other heretics like Arthur Koestler were saddled with (“I can taste the ashes but I cannot recall the flame,” Vivian Gornick once said of him). This is partly why the argument about Hitchens’ conversion has carried on so long – the story he gives is rife with justification but little reflection. Allow this, and it becomes much easier to notice the threads spanning his conversion. Hitchens’ language of emancipation, democracy, freedom, and rights during the War on Terror resembled that of his earlier days, though shorn of all meaning. The qualities he admired in dissidents like Havel, Brandt, and Papandreou could in turn be invested in Chalabi, though with his credulity intact. His internal logic, in a way, was impeccable; its defect was to interact with reality only occasionally. And it is a reality made poorer and more unsafe because of Ahmed Chalabi and Christopher Hitchens’ efforts, a reality we now have to live in, and they do not.

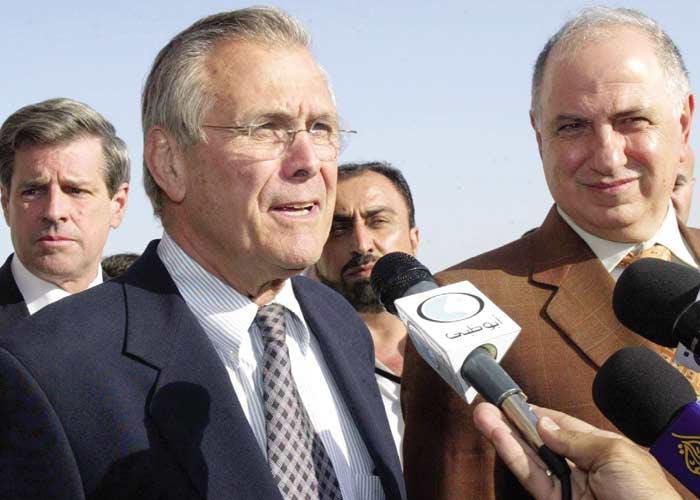

It is past threshing season. The bitter harvest has come in. In America’s dominion, the yield overseas is mashed flesh, scarred minds, anguish compensated for with pitiful payouts, and an unknowably large death toll. Inside the metropole, the architecture of what Spencer Ackerman called the “reign of terror” housed the most penetrating domestic panopticon ever constructed – a Stasi in all but name, rife with informants; a regimented bureaucracy of assassinations wedded to a shadow regime of deniable ‘black sites’ with their own clique of trained-up torturers; the militarisation of migration and the criminalisation of an entire faith; a programme of looting that shifted US$6 trillion to men in uniform and their leech-like auxiliary of contractors, and a total derangement of the culture. Atop it all were people like Donald Rumsfeld who, when confronted with reports of detainees tortured with “stress positions,” shrugged and dismissed it by saying “I stand for eight to ten hours a day.” Bitchiness mingled with cruelty: now there was an auguring of our present age.

[1] The sources for these quotations are, in order, Steve Coll in The Achilles Trap, Coll again, Aram Roston in the biography The Man Who Pushed America to War, Roston again, Graydon Carter, Newsweek, and Paul Wolfowitz.

[2] Stephen Phillips, the unknown slated to write one for WW Norton with a very bad title, was apparently scared off by the barricades thrown up by Hitchens’ widow Carol Blue and agent Steve Wasserman. The three titles are: Richard Seymour’s Unhitched: The Trial of Christopher Hitchens (2013), Ben Burgis’ Christopher Hitchens: What He Got Right, How He Went Wrong, and Why He Still Matters (2021), Matt Johnson’s How Hitchens Can Save the Left: Rediscovering Fearless Liberalism in an Age of Counter-Enlightenment (2023).